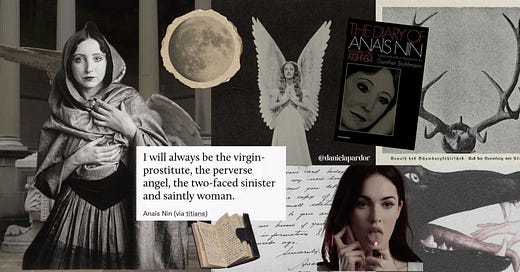

‘I will always be the virgin-prostitute, the perverse angel, the two-faced sinister and saintly woman’ is a quote that has haunted me ever since I read it on Henry and June by Anaïs Nin. An author plagued with controversies but who, particularly since the 1960s, has been considered a feminist icon of women’s sexual liberation.

The Unexpurgated Diaries of Anaïs Nin, as infamous as they may be considered, have become a prime example of a feminist literary tool. They showcase a woman in full control of her narrative and within a safe space to explore her darkest thoughts and desires. The equivalent to religious confession in the dimly lit, incense filled, walls of a church. It is within these diaries that Anaïs Nin vividly paints the picture of the perverse angel, the virgin-prostitute, a dichotomy that the writer struggles with both in her personal and fictional world.

The word ‘perverse’ immediately conjures a dark, evil, headstrong quality which contrasts the idea of an ‘angel’. In fact, often female qualities that go beyond the confines of the culturally accepted femininity, are considered monstrous. A likely reason may be that femininity is often understood by society within the ideals of passiveness and submissiveness. By comparison, Nin viewed creativity as a masculine trait influenced by how male authors in her circle, like Henry Miller, treated creative women. Miller's wife June, for instance, was often demonised for her creative pursuits. She was repeatedly used by Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin’s husband as a cautionary tale for Nin. A monstrous creature that Nin ought not to become, and yet, one that Nin couldn’t help but be captivated by.

The perverse angel serves as a symbol and archetype for the inner conflicts women still face in todays society, and which are still prominent in both literature and cinema. You are either a good girl or a bad girl, prude or slutty, innocent or dangerous. One or the other, but rarely both. Hence, when a woman has personal ambition and desire, she crosses an invisible line that ultimately denotes her in a negative, monstrous manner. A slippery slope that celebrities, such as Taylor Swift, have been navigating against her critics for the past few years. It is safe to say that this oversimplified categorisation of women is boring at its best and reductive at its worst. Now more than ever, depictions of female characters are evolving into what seems to fit Nin’s idea of the ‘perverse angel’ - an archetype that captures the duality of women. Look no further than Camilla Macaulay from Donna Tartt's 1990 novel ‘The Secret History’, the 2009 cult classic film ‘Jennifer's Body’, and the more recent 2022 film ‘Pearl’, for prime examples of this.

Richard Papen, Donna Tartt’s narrator in The Secret History, alludes to the virgin-prostitute conundrum expressed earlier by Nin when he tells us his feelings about Camilla: ‘She was a living reverie for me: the mere sight of her sparked an almost infinite range of fantasy, from Greek to Gothic, from vulgar to divine.’ Perhaps Camilla’s complex depiction was a conscious effort from Tartt’s point of view. On the one hand Camilla is ‘a slight lovely girl who lay in bed and ate chocolates’, but at the same time she is as curious and drawn to the dark side of intellectualism as her male counterparts. In this way, the ‘perverse angel’ archetype fits Camilla as she exemplifies the duality of women, ethereal and sinister. As the group commits murder under morally questionable lines of reasoning, Camilla remains poised and stoic, eerily composed. A paradox between her beautiful exterior and her impenetrable personality. This subtle portrayal offers a glimpse into Camilla’s complexity and exploration of girlhood - even if under the rose-tinted male gaze of Richard Papen. She navigates her intellect in a role that is equal to her male peers. She is both light and dark in a morally corrupt world of academia.

The notion of innocence corrupted at the hand of ambition is also seen in Pearl, a 2022 film co-written by Ti West and Mia Goth. Pearl is a young girl leading an isolated life at a farm in Texas, looking after her parents. Full of glamorous aspirations, she dreams of silver screen stardom. This tension is central to the film, as Pearl’s ever-growing desire to leave her small town life continually tests the limits of what she's willing to do to achieve her dreams. This ambition is manifested in increasingly violent and destructive ways, signalling the loss of her doe-eyed innocence.

The Horror genre, in particular, frequently features female protagonists with fully fledged, complex personalities and female audiences flock to see it. With the rise of A24’s brand of horror, and so called elevated horror, are these the most authentic portrayals of female characters we have? It has certainly provided a sense of escapism. Yet, most importantly, in a world where women often live in fear of violence, horror has restored the power women lack in real life - at least for the duration of the film.

Shifting our focus to 2009, while still exploring the horror genre, we find the now cult classic Jennifer’s Body starring Megan Fox. As if in an attempt to atone for our past misjudgments, society has collectively decided that this story by Diablo Cody was simply ahead of its time. And well, going by the terrible reviews at release, it definitely was. Megan Fox was the ultimate hot girl, and instead of being sexy, the film portrays her as a monster taking part in cannibalism. The audacity to go against the male fantasy! But it is through these depictions of the monstrous feminine that we often find the duality of women. One that doesn’t label them as just ‘good’ or ‘bad’ girls. Megan Fox’s character, Jennifer Check, embodies the ‘perverse angel’ archetype as she exudes femininity whilst also being dangerous. Through her character, Fox reclaims ownership of her sexuality and how it is perceived by society.

The notion of the ‘perverse angel’ doesn’t only apply to fictional characters, but also reflects the real life experiences of female writers. The Diaries of Anaïs Nin are a powerful material to understand the social environment and the fragmented mental state of the author. In essence, Nin tries to come to terms with her own creativity and the fact that it brands her as less desirable in the eyes of men, who develop an anxiety towards the newly found autonomy of women in both the social and literary spheres of the 1930s to the 60s. A time when the notion of reader, writer and critic was inherently male.

Even in today's world, writing remains a paradoxical act for women—simultaneously innocent and potentially dangerous. When a woman writes and delves into her deepest and darkest thoughts, it can be branded as perverse. But perhaps, this is changing. As more authors and filmmakers, such as the ones explored today, continue to challenge the one-dimensional portrayals of women, the traditional narratives of the virginal ‘good girl’ and the dangerous ‘femme fatale’ will hopefully fade into oblivion.